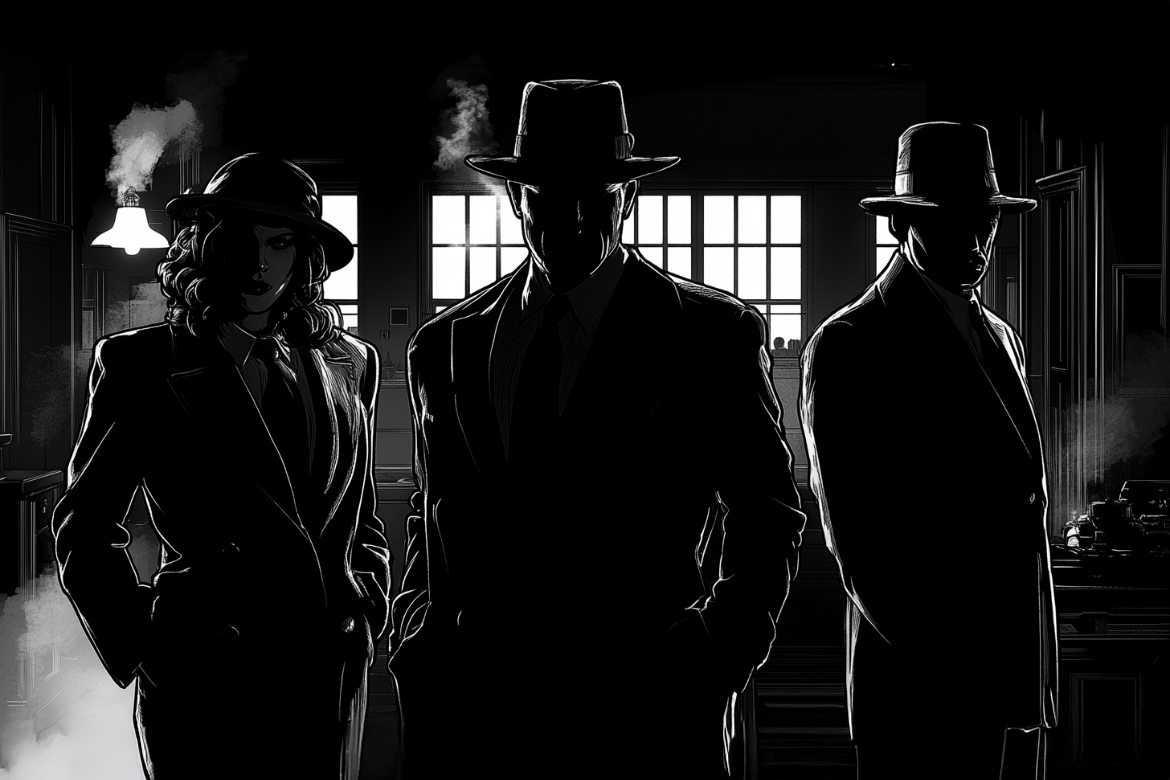

Characters are at the core of noir fiction. The shadowy, morally ambiguous world of noir is populated by deeply flawed, enigmatic figures whose personal struggles drive the narrative forward. To craft an engaging noir story, it’s essential to develop characters that are as complex and layered as the plots they navigate. This chapter will guide you through creating the protagonists, antagonists, and supporting characters that define noir fiction, emphasizing their psychological depth, moral ambiguity, and intricate motivations.

1. The flawed protagonist

At the heart of every noir story lies a protagonist who is anything but perfect. Noir protagonists are antiheroes—characters whose imperfections, inner conflicts, and dubious morals are central to the story’s appeal. Here’s how to craft an engaging noir antihero:

Flaws are fundamental: A noir protagonist’s flaws are not incidental—they are the heart of their character. Whether it’s alcoholism, greed, an obsession with justice, or an inability to trust, these flaws should impact their decisions and the story’s progression. For example, Mike Hammer in I, the Jury is driven by his relentless pursuit of justice, but his brutal and often violent methods highlight his deep flaws and willingness to cross ethical boundaries to achieve his goals.

Complex motivations: Noir protagonists rarely act out of pure altruism. Instead, they have layered motivations that often include personal gain, revenge, or guilt. In Nightmare Alley, Stanton Carlisle is driven by ambition and a hunger for success, using deceit and manipulation to rise through the ranks of the carnival world. His motivations, ranging from a desperate desire for power to a yearning for respect, keep readers on edge, never knowing when his schemes will come undone.

Inner conflicts: A great noir protagonist is constantly at war with themselves. Their moral compass is tested repeatedly, and their internal struggles often become central to the plot. In Out of the Past, Jeff Bailey tries to leave behind his criminal past, but his sense of loyalty and unresolved emotions pull him back, ultimately leading to his downfall. This internal battle between wanting to do right and being drawn to the darker side of life is what gives noir protagonists their depth.

2. The Femme Fatale

Noir fiction wouldn’t be complete without the archetypal femme fatale—a character who embodies danger, allure, and complexity. However, the femme fatale should be more than a mere trope; she should be a fully realized character with her own desires and depth.

More than a seductress: A well-crafted femme fatale is not just there to tempt the protagonist—she has her own ambitions, vulnerabilities, and reasons for her actions. Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity is not merely manipulative; her actions are driven by a desire for freedom and control in a world where she feels powerless. By giving her motives beyond mere greed, she becomes a character that readers can understand, even if they don’t condone her actions.

Ambiguity in intentions: The femme fatale often blurs the line between victim and villain, making her intentions difficult to read. In Gilda, Rita Hayworth’s character oscillates between vulnerability and manipulation, keeping the protagonist—and the audience—guessing. This ambiguity is crucial, as it adds layers to her character, making her both compelling and unpredictable.

Emotional complexity: While the femme fatale is often seen as manipulative, she can also be emotionally complex, capable of genuine moments of vulnerability. In Body Heat, Matty Walker manipulates her lover into committing murder, but her motivations are fueled by desperation and a genuine desire for a better life. These moments of vulnerability make her character more rounded and the narrative richer.

3. The antagonist

In noir fiction, antagonists are not always evil for the sake of being evil. They often serve as a reflection of the protagonist’s own flaws and desires, providing a dark mirror that forces the protagonist to confront themselves.

Shared flaws with the protagonist: The antagonist in a noir story often shares key traits with the protagonist, making their conflict deeply personal. In The Third Man, Harry Lime is charming, intelligent, and morally corrupt—qualities that make him both appealing and repulsive to his old friend, Holly Martins. The antagonist’s actions often represent the path the protagonist could have taken, which adds a layer of introspection to their conflict.

Relatable motives: A noir antagonist should have motivations that make sense, even if they are morally questionable. In Chinatown, Noah Cross is motivated by power, control, and legacy. His actions are monstrous, but his motivations are understandable within the framework of his worldview. This complexity makes him a more compelling antagonist, as he is not simply an obstacle but a character with a clear, albeit twisted, purpose.

Moral ambiguity: Just as the protagonist is morally ambiguous, so too should be the antagonist. Their actions should challenge the reader’s perception of right and wrong, and perhaps even evoke a level of sympathy. In L.A. Confidential, Captain Dudley Smith is corrupt to his core, but he genuinely believes in maintaining order—even if that means breaking the law. This belief system creates an antagonist whose evil is not clear-cut, adding depth to the story.

4. The supporting characters

Supporting characters in noir fiction play crucial roles in adding depth and complexity to the story. They can serve as allies, obstacles, or even foils to the protagonist, each contributing to the overall atmosphere and tension.

The trusted ally who betrays: Noir thrives on betrayal, and one of the most effective uses of supporting characters is to create an ally who turns on the protagonist. In The Maltese Falcon, Brigid O’Shaughnessy initially appears to be a client in need, but her betrayal is central to the narrative, deepening Sam Spade’s distrust and cynicism.

The innocent in a corrupt world: Including a character who is seemingly innocent can serve to highlight the corruption of the world around them. In Chinatown, Evelyn Mulwray initially appears to be a victim of circumstances beyond her control, and her innocence contrasts sharply with the corruption of her father and the city itself. This juxtaposition emphasizes the bleakness of the noir world, where even the innocent are not spared.

Foils to the protagonist: A foil character serves to highlight the protagonist’s traits by contrasting with them. In L.A. Confidential, Bud White and Ed Exley serve as foils to each other—White is driven by emotion and brute force, while Exley is cold, calculating, and ambitious. Their differences force each to confront their own weaknesses and ultimately grow as characters, adding depth to the story.

5. Motivations and backstory

To create truly complex noir characters, it’s essential to delve into their motivations, backstories, and moral ambiguities.

Layered motivations: Every character in noir should have multiple motivations that drive their actions. A detective might be seeking justice, but they might also be driven by revenge or guilt. In The Long Goodbye, Marlowe’s loyalty to his friend Terry Lennox keeps him involved long after any rational person would have walked away, showing that personal loyalty often overrides logic in noir.

Detailed backstory: The past looms large in noir fiction, often dictating the actions of the present. Give your characters a backstory that haunts them—mistakes, regrets, or lost loves that shape their current worldview. In A History of Violence, Tom Stall is a family man whose violent past resurfaces when he stops a robbery, leading to the unraveling of his carefully built life. His attempts to protect his family while dealing with his former associates show how past actions inevitably catch up, adding depth and a tragic sense of inevitability to his character’s journey.

Grey zones: No character in noir should be entirely good or bad. Each character’s actions should be colored by shades of gray, making it difficult for readers to fully align with or against them. In Gone Girl, both Nick and Amy Dunne exhibit morally questionable behavior—Nick is unfaithful and evasive, while Amy’s manipulations are extreme and ruthless. This ambiguity keeps readers engaged, as they must constantly reevaluate their opinions of the characters.

Creating complex characters in noir fiction means embracing their flaws, moral ambiguities, and the shadows that drive them. The protagonist, femme fatale, antagonist, and supporting cast all contribute to the intricate dance of deception, betrayal, and flawed humanity that defines the genre. By focusing on layered motivations, rich backstories, and the tension between right and wrong, you can craft characters that are not only compelling but also integral to the dark, twisting plots of noir fiction.

Remember, in noir, every character is both a victim and a perpetrator of their circumstances. They are driven by desires they can’t fully control and haunted by past actions they can’t escape. Embrace this complexity, and your characters will breathe life into the shadows of your noir narrative, leaving readers captivated by their depth and haunted by their choices long after the story ends.